Firstly, if you’ve been following this arts/big data series then apologies for the brief hiatus – life got in the way. The good news is that you’ll have had a chance to catch up on all the reading material in the link dump of articles, blog posts and reports. In this post, I’m going to take a more in-depth look at a single report.

Counting What Counts: What big data can do for the cultural sector was written by Anthony Lilley and Professor Paul Moore and published in February 2013. You should read the report in full but, on the basis that few people will bother, here’s a rough paraphrasing of the executive summary…

Counting What Counts: a very short summary

The tone is bullish about the opportunities presented by big data, critical of the current situation and strikes a very forthright tone:

The current approach to the use of data in the cultural sector is out-of-date and inadequate. The sector as a whole and the policy and regulatory bodies which oversee it are already failing to make the most of the considerable financial and operational benefits which could arise from better use of data. In addition, a significant opportunity to better understand and possibly increase the cultural and social impact of public expenditure is going begging.

There are barriers to the use of big data approaches in the cultural sector:

- The funding environment means that reporting is seen as a burden, something that’s partly to do with a philosophy of dependence, subsidy and market failure.

- There is limited strategic understanding of, or interest in, the use of data at senior levels.

A three-part solution is proposed:

- Organisations should audit their approach to their data and set out a plan for improvement to get their houses in order. This will provide a foundation for ongoing data-centric work.

- Pathfinder projects should be funded to explore new approaches to using data.

- Capacity-building projects should help policy makers, funders and boards get to grips with data.

A note about this review

Simon Kirby is a scientist who, in a recent Guardian piece comparing art and science, said science is “all about surviving the gauntlet of people trying to tear your ideas apart – that doesn’t happen with an arts audience.”

In that general spirit, I hope this review serves some use. There are very few experts in this area and most of the ‘discussion’ seems to be dominated by marketing collateral of one sort of another. There’s a comments field below and I’d love people to put me right where I’ve slipped up.

Review of Counting What Counts

TL;DR

Although some of the recommendations in this report are pretty sensible, they sit on very shaky foundations. If policy and funding decisions are being made on the basis of this kind of thing then I’d be concerned.

To elaborate, here’s what I thought was good about the report and what I thought was bad.

The good

- I’d wholeheartedly endorse several of the recommendations. This is a fascinating, emerging area and with plenty of difficulties and uncertainties yet to be resolved. Organisations could very probably do more with data and their boards, funders, etc could very likely do more to support them in that.

- It’s good to see a report putting this subject on a few peoples’ radars.

Ok, it’s a short list (and I might come back and add to it) but, in fairness, those two are biggies.

The bad

This is a longer list. I’ve expanded on each of these points below:

- By ‘the cultural sector’ the report seems to mean Arts Council England’s National Portfolio Organisations. This isn’t made explicit but it’s pretty evident from context. The report therefore seems to have a very narrow focus, the reasons for which aren’t made clear (not that it would necessarily be a bad thing).

- Big data – a wooly term at best – isn’t defined with much/any clarity. In fact, there are plenty of references to data that isn’t ‘big’ in the slightest.

- I think there’s some conflation going on between the concepts of big data and data-driven decision making. There’s certainly overlap, but this report dodges back and forth between the two a few times.

- The report tends to focus on the analysis of data, whereas discussions of big data beyond the arts sector are just as concerned with the challenges of collection, management, search and storage. There’s not much about these other aspects in the report.

- For all the harsh (yet not particularly specific) criticism of arts organisations’ current use of data, there’s little appreciation of why they’re failing (in the authors’ eyes, at least).

- I’d like to have seen more (some?) evidence of the types and extent of the benefits that may be derived from better approaches to data.

- More specifically, I’d have liked to have seen what the commercial sector are doing that’s so great – what obstacles have they overcome (learning that the arts sector can piggy-back on) and what challenges are remaining?

- A further point on that – what differentiates the cultural and commercial sectors in terms of data use? What challenges can the cultural sector leave to the commercial sector, allowing cultural sector funding to be used more effectively?

- One last thing on the commercial sector – comparisons with Google, Amazon and Facebook really aren’t very helpful and they’re certainly not realistic.

- Looking at the list of experts consulted, I didn’t see anybody who works hands-on with data in an arts context. Not day-to-day, at least (although apologies if I missed anyone, but I did Google the names I didn’t recognise). This is a pretty shocking omission and might explain a raft of things, not least the next few items.

- The ‘technical experiment’ is just a bit embarrassing. It’s amateurish and shows a complete lack of understanding of the subject matter.

- All that weird stuff about a UK Arts Data API… It’s like someone’s used one of those buzzword generator things.

- The ‘Data Maturity Model’ isn’t great either. I can see the appeal of having one number that sums up an organisations’ approach to data, but it’s totally divorced from reality, of no practical use and should be jettisoned.

- I feel bad for stamping on optimism, but more data isn’t the answer to everything – in fact I think that’s a dangerous route to go down.

- I didn’t fully get to grips with the long discussion about cultural and public value

That’ll do. I had a few more gripes but I think those are the more substantial ones. If you’re interested, I’ve put some meat on the bones below. Like I say, the point of this is that discussion is good – comments are open for anyone wanting to chip in, correct me or point out something else.

1. What is the arts and culture sector?

This doesn’t seem to be defined all that clearly. There’s talk about media and TV in there but, with all the talk of funding and reporting throughout, I get the impression that this report is mostly aimed at the Arts Council’s National Portfolio Organisations, rather than the much wider arts ecology.

I’m not sure how much of this applies to smaller players in the cultural ecosystem (there are so many one-man bands and SMEs) as well as the more commercial organisations that don’t receive subsidy (ie West End theatre, the Royal Albert Hall, etc). I’m not sure whether this report is meant to apply to the museums and heritage sector. Maybe.

I get that it’s easier to coerce a group of organisations that are beholden to a major funder, but if the report was just meant to concentrate on NPOs then it could’ve been more explicit about it. That level of focus might have been helpful.

2. Defining ‘big data’

There’s not really much of an explanation of what big data is either. Fair enough, it’s a pretty wooly term, but two broad approaches seem to be coming out. Either:

- It’s all relative so, if you’re dealing with lots more data than you’re used to, then that’s enough to consider it to be ‘big’; or

- It’s only big data if it poses you serious logistical problems, taking up loads of space in data warehouses and taking ages to crunch through.

To my mind, the first isn’t necessarily big, it’s just bigger. If that means the wider big data conversation is irrelevant to you then that’s nothing to be ashamed of – count yourself lucky. Whereas, if the sheer quantity of data you have gives you headaches to do with storing, searching through and analysing it, if you long since gave up on using a laptop, Excel and Google Docs and are trying to get your head round Redshift, Big Query, Hadoop and data warehouses, then I think it’s fair to say you’re in the realms of big data.

Anyway, I didn’t see much attempt to define the subject of the report beyond a reference to Gartner’s 3 V’s model of volume, velocity and variety.

This is a problem because, without some kind of filter or cut-off, references to things that surely aren’t all that ‘big’ sneak in and muddy the waters. References to reading out results from people playing along at home on Million Pound Drop are a case in point.

It’s also an issue because when you’re recommending funding and R&D in this area and your recommendation is (apparently) acted upon, then it would be fair for people to turn around and say ‘This is all well and good but what exactly are you talking about?’

3. The overlap between big data and data-driven decision making

Following on from this, I didn’t think there was a clear enough delineation between these two concepts. There’s plenty of overlap between the two, of course, but I think ‘Counting What Counts’ would’ve been much stronger concentrating on the latter, rather than the former.

That would’ve given the authors plenty of opportunity to talk about potential sources of data, some of which may well be ‘big’. I think that report would’ve had much wider applicability and would’ve had a more solid foundation.

4. All about the analysis – what about the other challenges?

Maybe the report works on the assumption that the analysis is the bit that’s particular to the arts and culture sector, whereas all the other big data challenges will be addressed by the commercial sector. If that’s the case then it’s not stated anywhere.

Thing is, if the commercial sector does come up with some clever solutions, what are the chances that the cultural sector will be able to afford them? For a bit of context to that, most organisations get by with the free version of Google Analytics – name a cultural organisation in the UK that could justify a $150k annual outlay on the Premium version. The cultural sector is just not a big player in this area.

I don’t even buy the idea that the commercial sector will solve the other parts of the puzzle. The cultural sector will have it’s own particular issues when it comes to capturing, licensing or storing the amount of data we’re talking about here.

The skills shortage is going to be another massive problem. To be fair, this is mentioned briefly:

organisations such as Channel 4 are already battling with the challenge of employing enough data scientists to help them analyse and then create strategic narratives around their data. People with such skills are in high demand and are expensive to hire

But, other than recommending some capacity building and some R&D, there are no suggestions as to what might be done about this.

It’s also interesting that the report mentions a recent report from the McKinsey Global Institute, quoting the potential benefits of big data. What isn’t mentioned is the same report’s utterly damning assessment of the entertainment (arts, music, film, gaming, etc) industry’s ability to take advantage of these, given competition for data analysts that will come from resource-rich industries where there is an even greater opportunity for data to impact on the bottom line. I’ve written about that before.

The thing is, the nonprofit sector has already been left to pick up scraps from the bigger boys. Not that I’m the slightest bit critical of projects like Data Dives – I think they’re superb – I just mention it because it’s just an indicator of where the cultural sector stands in the pecking order.

5. Additional challenges specific to arts organisations

I don’t mind a bit of finger-pointing, but I’m not convinced there’s been a proper appraisal of the situation. Here’s the quote that got my back up (and I don’t even work at an arts org):

The sector currently largely addresses data from too limited a perspective. Too often, the gathering and reporting of data is seen as a burden and a requirement of funding or governance rather than as an asset to be used to the benefit of the artistic or cultural institution and its work. This point of view is in danger of holding the sector back. It arises partly from the philosophy of dependence, subsidy and market failure which underpins much of the cultural sector including the arts and public service broadcasting.

Where’s this come from?

Firstly, I’m pleased to say that I don’t see that in most of the clients I work with (who, admittedly, tend to be the larger organisations). Those organisations often have significant commercial income streams and smart people in place to maximise them. They don’t tend to miss a trick, even though they often have to work with limited resources.

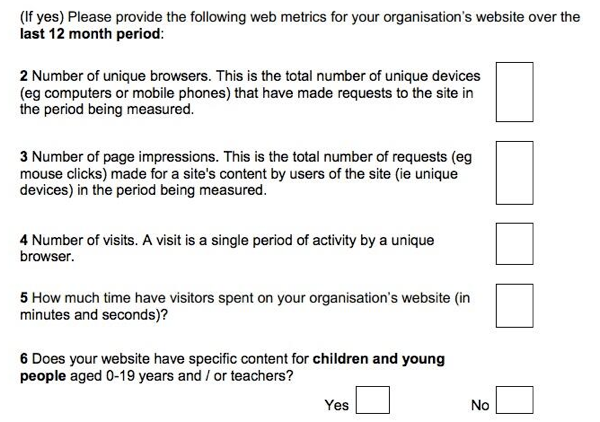

Secondly, let’s take a quick look at the website metrics the Arts Council asks their National Portfolio Organisations to report on – part of the reporting that’s apparently such a burden (with thanks to Sam Scott Wood for the pic):

Well of course that’s a burden! Reporting those figures is (variously) pointless, impossible and ridiculous. It’d be more worrying if people didn’t see reporting those things as a burden.

The report says:

There is a significant opportunity here for organisations such as Arts Council England and Nesta to lead the way by reforming their own use of data and their expectations of funded organisations.

Damn right, although on the strength of this the Arts Council are the ones playing catch-up.

6. More on the type and the extent of the potential benefits

I’ll come back to this, but this wasn’t strong enough for me. Maybe it can’t be predicted without some serious R&D and that’s the point of the recent funding call. I dunno. Worth talking about though.

7. What is the commercial sector up to?

I read this:

It is high time for a step-change in the approach of arts and cultural bodies to data and for them to take up and build on the management of so-called “big data” in other sectors.

…and was left scratching my head. Is the commercial sector really that much further ahead? Econsultancy’s latest bit of research found that “Only one-fifth of businesses (20%) have a company-wide strategy that ties data collection and analysis to business objectives” and that figure has remained pretty constant for the past 5 years.

I suppose it depends who you’re looking at (see point 9 below).

I also have a serious issue with “take up and build on”. It’s a fact of life that the arts and cultural sector is going to be significantly outgunned when it comes to recruiting data analysts. As well as that McKinsey report mentioned above, take a look at what IBM are doing recruitment-wise.

8. Differentiating commercial and cultural approaches

I kinda covered this under point 4 when talking about how the commercial sector will pick up and solve some of the challenges presented by big data. However, there’s a whole other discussion to be had about how cultural organisations have different sets of priorities to commercial ones, and how this brings different considerations to bear. I might try and pick this up again when I’ve had more of a think about it.

9. Comparisons with the big boys

Speaking of comparisons with commercial organisations, name me an arts organisation that’s on the same scale as Google, Facebook or Amazon. Exactly. So why make the comparison? Most arts organisations are one-man bands and SMEs.

For instance, is it helpful to know that Google A/B tests hundreds of parameters a day? How does this translate to even the largest arts org? There’s a danger in assuming that there’s equivalence between a huge, pure-play online company and a physical venue.

10. The experts

There’s a list of interviewees and contributors at Appendix 3. It includes a significant number of TV people and very senior arts organisation figures. That makes sense, seeing as how the report is aimed at the kind of people who think strategically about this kind of thing. However, strikingly, I didn’t see any of the following on that list:

- Digital agencies that work with arts organisations day-to-day

- Ticketing and CRM providers

- Audience development agencies

- Anyone working specifically on big data-centric projects

In other words, nobody who regularly works with data in an arts and culture context was consulted. Which might explain a few things.

11. The technical experiment

When I was first flipping through the report, this is one of the first things I read through in any detail. This more than anything, blew my confidence in this report.

It’s lightly documented at Appendix 2. The gist is that the authors tried to create a rough prototype of a ‘Big Data Dashboard for the Cultural Sector’ which, it was suggested, would have some wide-ranging benefits for a broad range of users. I’m not sure whether any such users were consulted. I strongly suspect not, but you never know.

In fact, I’ve gone back and read this again and it’s absolute TEXTBOOK underpant gnome thinking:

- Show an ongoing, real-time and customisable basis data such as sales trends, ROI on campaigns, social media analytics, sentiment concerning individual cultural products and organisations plus sentiment and other trends over time, and algorithm-based suggestions and recommendations for further action (this list on p53)

- ?

- In doing the above, improve the resilience of arts and cultural organisations and sectors, the experience of consumers/citizens and the delivery of public/cultural value

The only possible response to this is surely “What ARE you talking about?”. And that’s before we point out what’s so clearly and obviously wrong about part 1 of that list.

Unfortunately the experiment ran into some pretty predictable problems and, instead of aggregating some potentially interesting data sources, it ended up just being a mash-up of a few common social media services’ APIs, although we don’t get to see the actual results.

Now, that sort of thing’s excusable for something knocked together at a hack day. However it’s surely not good enough when you’re trying to illustrate the point that data can drive valuable and needed insight.

Anyone with the slightest clue knows that you should identify a goal or a hypothesis, collect relevant data, analyse it, draw conclusions and then (if possible) act upon them.

That’s not what happened here though. They slapped a bunch of data together and then wondered why it didn’t provide any dazzling insights. It’s so frustrating to see. To be fair, elsewhere in the report it does say:

More data and measurement are not, by themselves, a solution to any particular problem. The potential for more data can, in some contexts, even become debilitating, especially if it is collected for the wrong reasons, in an inefficient way, poorly analysed or not acted upon.

I just wonder whether that lesson was learned before or after the experiment.

What’s more, it turned out that the APIs weren’t stable and there was too little useful documentation. Which basically betrays a fundamental lack of understanding and familiarity with this area.

This was the bit that got me – and frankly, looking back, I’m surprised I bothered reading on after this:

The second most significant challenge came about once the APIs were ‘plugged in’ and the scale of the data coming back became clear. Facebook and Google for example return an extensive amount of data and identifying the most appropriate fields for the dashboard became a time consuming task.

That’s right, the data turned out to be big. Who would’ve guessed?! FFS.

12. The UK Arts Data API

Sorry, you’ll have to forgive me, but I don’t even know where to start with this. It either shows a total misunderstanding or is wilfully bonkers. Presumably it’s the former.

UPDATE: It’s a week later and I’ve been puzzling over this, mostly because if I’m going to object to something then I should be more coherent about it. However, I still don’t get it. There’s some blurb on p.57 of the report that seems to suggest that an arts data API would be a good first step towards the ‘big data dashboard’ the authors are obsessed with.

The words ‘ensure maximum interoperability amongst cultural sector data’ are there in bold, but that’s a different thing, right? There might be some merit to that, but good luck getting a few hundred organisations to agree on that and implement the relevant systems.

I don’t know I’ve tried to work out what the report’s getting at with this, but it’s so vague and formless it’s like trying to nail jelly to a tree.

13. The Data Maturity Model

This is essentially a much simplified version of Stephane Hamel’s Online Analytics Maturity Model. The report says that you can characterise an organisation’s use of data as good, bad or ugly (allowing for some overlap between categories). I can see the desire to boil things down to a single indicator, but it goes way too far.

14. Data shouldn’t rule everything

There’s some suggestion that:

an education project might agree a set of criteria or search terms and track these in addition to the specific names of the project, the organisation, the key participants etc through a dashboard of measures which would also be combined with hard data from CRM systems wherever possible.

Is this seriously saying that an educational project must be talked about online for it to attract funding?

15. Social/public value

I admit I wasn’t massively interested in the discussions about investment/subsidy and cultural value. It felt like a dive down a particularly speculative rabbit hole.

For more on this area, I’d recommend reading Susan Oman’s own review of this report. She’s able to pick this apart much better than I ever could.

In conclusion

To my mind, many parts of the report show a poor understanding of the subject matter at a worryingly a basic level. In other places it’s not at all clear whether the authors have carried out much of an appraisal of the current position, either on the cultural sector side of things or the data usage side. There are some sizeable omissions too.

Despite that, several of the report’s recommendations are somehow perfectly sensible. For all my criticism, the key message of the report is one I’m more than happy to get behind. I’m a big believer that data could better inform those who work in the cultural sector, but I also see (on an almost daily basis) that there are significant obstacles to overcome in achieving that. I’m also keen on the idea that there are emerging techniques worth investigating to see what new types of value and insight they might provide.