Generally speaking, bigger websites are better. A large website means more pages to be picked up by search engines and presented in organic search results, hopefully resulting in more traffic.

Of course, if care isn’t taken to produce and organise content effectively, larger websites can become unwieldy, sprawling and directionless, filled with with poor quality, stale or duplicate content. That’s not so good.

I’ve been wondering – how big do arts organisations’ websites tend to be? Without access to their databases or content management systems, it can be hard to tell. However, it’s pretty easy to find out how many pages Google thinks a website has. I’ll explain how below.

Findings

So, of the arts organisations that I’m looking at in this series, who has the most pages indexed by search engines? Let’s have a look.

(Data captured on 6 February 2013).

What does this tell us?

Not a great deal, to be honest. Not at an overall level at least, because I think there’s something wrong here. It’s nice to have the context this data gives us but I think something’s going on to create those massive outliers. I’ll get on to that.

I’d have liked to have been able to prove a hypothesis that larger venues such as the Barbican and Southbank Centre would be near the top of the list, given the number of productions they have every year (they’re up there but not topping the list). Or maybe organisations that have digital/new media teams that produce large amounts of content might perform well. Or perhaps those who know how to deal with old/archived information properly (rather than deleting entirely from their site – a capital crime in my eyes).

What if there’s something skewing this data then? It might be worth taking a closer look at the pages that are being indexed for those larger sites to see if the numbers are being inflated somehow. Well, at a quick glance I can see that:

- Dates on BSO’s calendar seem to be being picked up.

- Pages on Opera North’s mobile site are being indexed.

- ENO have a big problem with duplication of content.

- Lyric Hammersmith’s calendar is being indexed too.

So maybe there’s something to that theory. Bear in mind that if your site is, in the eyes of the search engines, substantially made up of duplicate or poor quality content then Google, et al may well decide that they should send less traffic to your website. Maybe they’re doing this already.

As you can see, context is good but this kind of information’s really more useful when applied at the individual level. If my organisation was at either the high or low end of that table, or my number of indexed pages seemed off then I might want to do some investigating.

Why you should check your indexed pages

One of the first things you do as part of a search engine optimisation audit is to find out how many of the pages that make up a given website are being listed (or indexed) by search engines.

- Too few: It could be that you’re blocking search engines from crawling your website, or it could be that your site has been delisted for some reason.

- Too many: You could have an issue with duplicate content or URLs being indexed that shouldn’t be.

In either case, you’ll want to remedy the situation to prevent being penalised by the search engines.

How to check your indexed pages for yourself

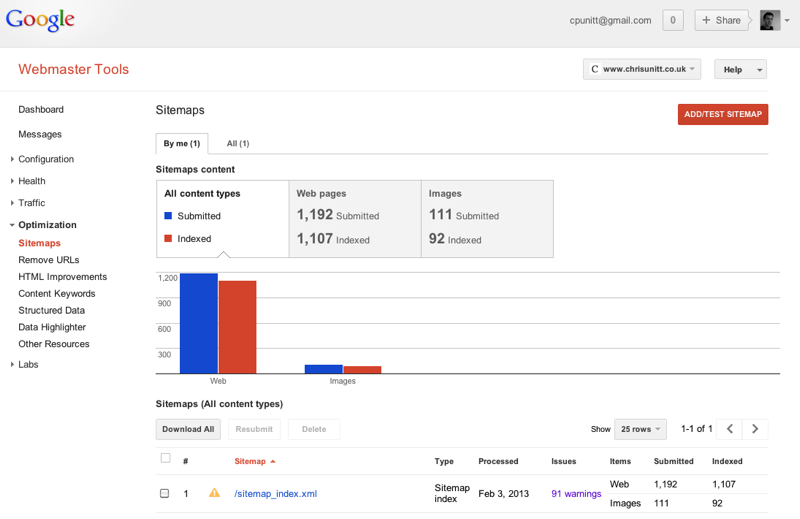

Google have a very handy thing called Webmaster Tools which is easy to set up and gives you all sorts of ways to check the health of your website. Under ‘Sitemaps’ you’ll be able to compare the number of URLs in your website’s sitemap with the number that have been indexed by Google.

For instance, for my website you can see in the screenshot below that 1,192 pages are included in the sitemap and 1,107 have been indexed. I’m also told that I have 91 warnings. I know that those all relate to URLs that I’m hiding from search engines on purpose (it’s a WordPress thing), so that’s all healthy.

By the way, you can and should hook up your Webmaster Tools account to your Google Analytics account. It only takes a second and is worthwhile doing.

How to check someone else’s indexed pages

I don’t have access to information from Webmaster Tools for all of these sites, so how did I get my data?

I’ve used two methods. To find the number of pages indexed by Google I just Googled ‘site:URL’ for each organisation and looked at how many results were returned. For instance, try clicking site:bsolive.com. At the time of writing, the figure is ‘about 634,000’.

In the fourth column in the table above I’ve also included data from a company called Majestic SEO. They’ve built a search engine which crawls the web and builds up an index of pages and the links between them. They then make this information available to others.

The data from Majestic SEO doesn’t seem to match up with Google’s all that often here but I wonder if that might point to the kind of issues I outlined above. Or maybe it’s a difference between indexed pages and URLs on a site (where URLs may include images, etc). Either way, I’ve included the data because it was easy enough to do. I’ll be using other data from Majestic SEO in later posts.

Recommendations

- Use Webmaster Tools to compare the number of pages in your sitemap with the number of pages indexed by Google

- If you spot a problem, take action to fix it – look for duplicate content and pointless pages (like every day in your calendar) being indexed

- Connect Webmaster Tools to your Google Analytics account.

- Commission a website/search engine optimisation audit to pick up anything that might be affecting your website’s performance.

The problem with Royal & Derngate

You may have noticed that, according to my research, Royal & Derngate in Northampton only have two pages indexed by Google. A visit to their site shows that they have plenty more pages than that, so there must surely be some mistake. Unfortunately not.

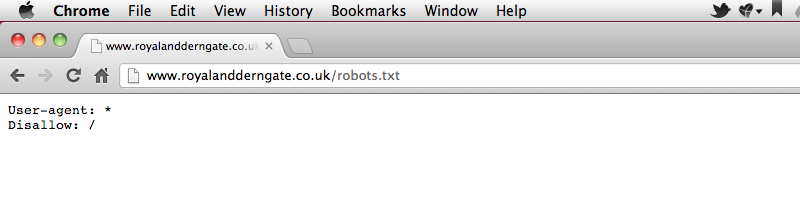

Royal & Derngate are blocking search engines from indexing their site.

This is a very bad thing. They’re using a robots.txt file (http://www.royalandderngate.co.uk/robots.txt)to tell search engines not to visit the site. You can find out more about how this works at robotstxt.org. Here’s what it looks like:

Now this must’ve been done by mistake. There are reasons for hiding websites from search engines but I can’t see how any of them would apply here. Mistakes happen and that’s fair enough, but I’m going to stick my neck out and assume a few things here:

- Nobody’s hooked up Webmaster Tools on this site, otherwise this would’ve been flagged straight away.

- They’ve never commissioned a website or search engine optimisation audit, or this surely would’ve been caught.

- Nobody’s looking at their Google Analytics, otherwise they’d have noticed a total lack of organic search traffic.

- Or maybe someone is looking at their GA stats, but they don’t know what a ‘normal’ level of organic search traffic looks like.

Thing is, who does know what a normal level of organic search traffic looks like for a theatre? Well, me, but then I have access to lots of theatres’ stats. My point is, it’s not info that’s shared around very much.

Just to underline what an important issue this is, I’ve just checked some stats for some clients and found that 47-58% of their online sales come via organic search. I really should be charging someone for flagging this up.

Instead, Royal & Derngate: please make fixing this a priority. UPDATE: I’m pleased to say the folks there have been in touch to say they’re fixing this (and I did drop them an email about it to let them know).

This post is part of a series called Arts Analytics where I’m using digital metrics to see what a group of arts organisations are doing online. If that’s your sort of thing then sign up for the free Arts Analytics newsletter for more of the same.

If this was useful then I’d be really grateful if you shared it with others.

Another fascinating post Chris.

Some of these problems (such as the very specific robots.txt issue at the end of the article) could be fixed in five minutes. From my own experience working in arts venues, though, it could take anywhere from five minutes, to five months, to never being fixed. It depends on the culture of the organisation, the skills of those within the organisation, and ‘legacy’ issues.

It could be that someone has the skills, but can’t allocate the time; it could be that they lack their managers’ trust to “touch the site”. And it’s not necessarily that an organisation lacks someone with the skills to spot and fix problems: it could be that control over their site is held by some distant figure with bigger priorities (e.g. a local council’s web team).

It may even be that those controlling the budgets need someone who understands the problem to step up and make the case for spending money – which again could be a time and confidence issue.

I really hope we’ll see organisations start taking ownership of their sites – not just treating ‘the website’ as a separate, static thing that you shove events on and that gets a refresh every couple of years, but something dynamic that needs to be monitored and optimised all the time.

A lot of issues could be solved by thinking ‘digital’ from the outset: weaving it into the marketing fabric – a starting point, rather than an afterthought. I sense those in charge are starting to think this way, in some orgs more than others – hopefully it’s a trend that will continue.

Response from our agency re Opera North’s ‘double indexing’ (not actual double-counting):

“Googlebot has crawled and indexed all of the Opera North mobile site pages. Google will show all of the Opera North pages, including mobile pages, when you search ‘site:operanorth.co.uk’. However, this does not mean that there are duplicate page errors.

Having the (m.) change in URL shows the Googlebot that it is a different (mobile) site to the original site and will not create a duplicate page error.

We have run a test this morning using SEOmoz to check for any duplicate page errors due to the mobile site. The test shows there are no mobile duplicate page problems.”

I’d have thought you’d only want the m. pages to be displayed to a) folks on mobiles who are redirected from the main site, and b) desktop users who choose to go to the mobile site directly. I wouldn’t have thought you’d want general search traffic to go to the mobile site.

Maybe it’s just not such a big deal, with main site URL’s turning up higher in SERPs. It explains why that site seems so much bigger than some others though.